Reimagine Language Education

Teaching English as a second or foreign language holds profound significance for me. It is disheartening to hear that some view this field as an “easy” fallback career, a perception that affects the intellectual rigor and transformative potential inherent in language education. Such a mischaracterization not only devalues our work but also reinforces outdated power structures that restrict English to certain narrow groups of “native” English speakers. I believe we must redefine our discipline by embracing a communicative approach to teaching, learning, and assessment, one that positions English as a truly global language and honors the diverse backgrounds of all learners (Brown & Lee, 2015).

1. Real-World Meaning and Communicative Focus

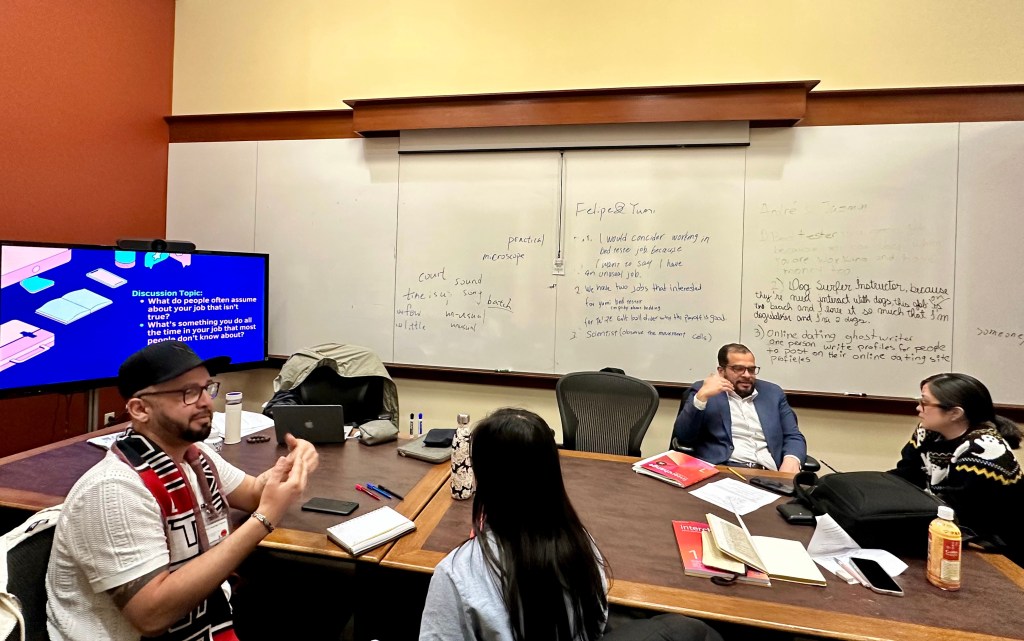

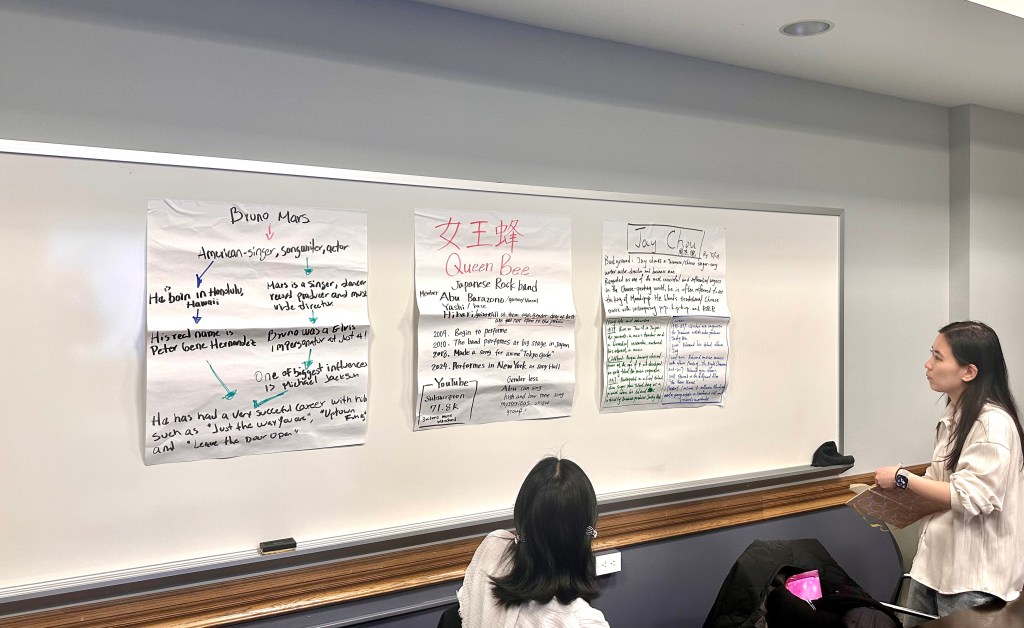

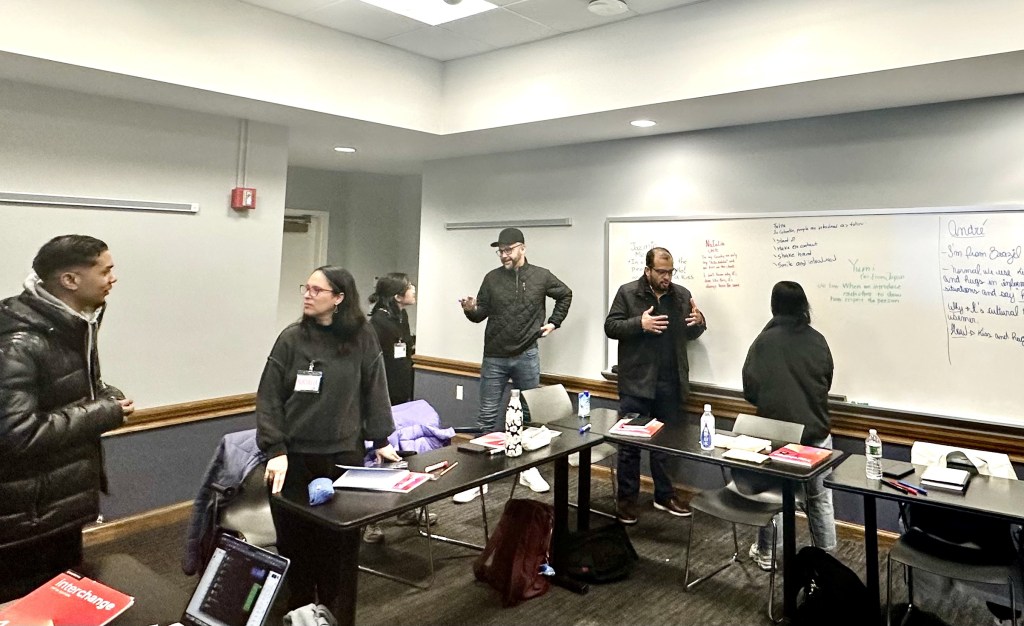

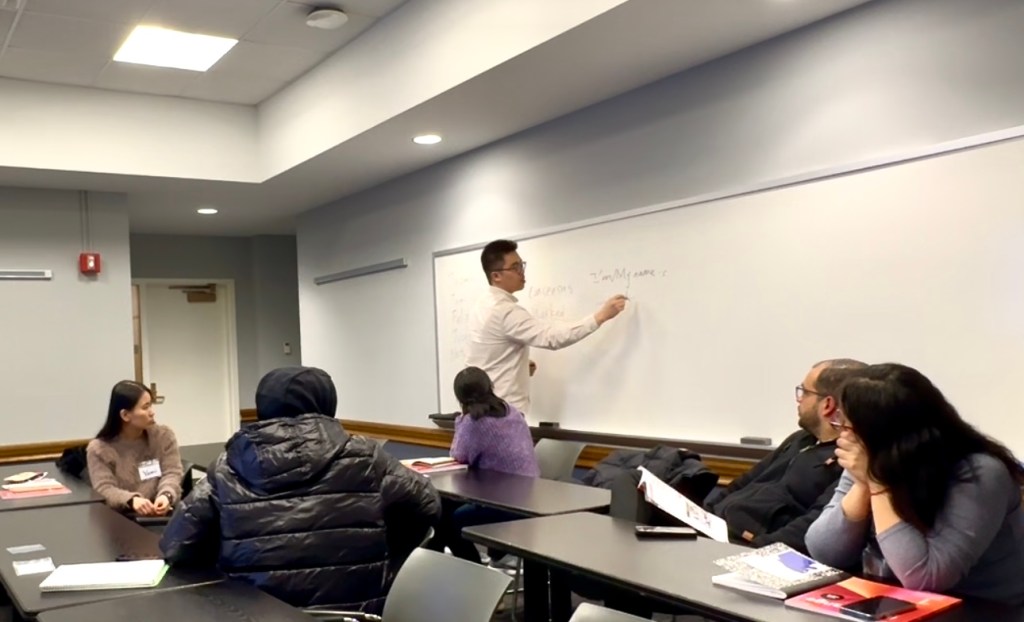

To me, language is truly meaningful only when it is used in authentic, real-world contexts—whether in writing, speaking, listening, or reading. Teaching solely for short-term outcomes, such as exam preparation, often results in a fragmented understanding that does not support long-term communicative competence. I always aim to design my classes in a way that students walk away with tangible skills directly applicable to daily life. For example, in my Elementary 1 class at Teachers College, a module on self-introduction, traditionally concentrated on teaching rigid structures (e.g., “My name is…,”, “I’m from…”), is expanded in my classroom to reflect the complexities of real-world communication. As in everyday situations, introductions rarely happen in isolation, they’re often shaped by interruptions, background noise and diverse contexts. They might take place online (e.g., email, Zoom) or in-person, with each setting influencing what & how we introduce ourselves. I do not want my students to simply accumulate a notebook of grammatical rules without understanding how to apply them. While I acknowledge the indispensable role of grammatical and lexical resources in acquiring language, I integrate these elements within a communicative framework. I employ strategies like vocabulary pre-teaching, with subsequent elicited grammar instruction that follows the primary focus on meaningful communication. This approach is rooted in the principles of Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) and Task-Based Language Teaching (TBLT), ensuring that language learning is both functional and contextually relevant (Ellis, 2015).

2. Catering to Individual Differences and Needs

Through years of teaching across China and the United States, from K–12 classrooms and online platforms, from extracurricular tutoring centers to postgraduate courses for engineering professionals. I have learned that the first and most crucial step in effective instruction is assessing each student’s unique needs, drawing inspiration from Nunan’s (2004) needs-based approach to content selection. Every learner comes with a distinct purpose for improving their English proficiency. Some students, such as those from affluent backgrounds attending summer programs abroad, may seek an opportunity to explore a new environment like New York City, while busy professionals, after a long day of work, attend evening classes to enhance their communication skills for career advancement. Others, particularly those from EFL contexts, might focus intensively on TOEFL/IELTS preparation over several months to meet university requirements. I approach each individual with an open mind, ensuring that I understand their goals and perspectives before proceeding with tailored instruction. Moreover, I recognize that factors such as a student’s native language, cultural norms, language exposure, and the typological differences between their first language and English influence learning. I also pay careful attention to details such as personality traits, whether a student is shy, outspoken, or perfectionistic, and to their specific learning preferences and proficiency levels. This enables me to design differentiated instructional strategies and assessment materials that meet the diverse needs of my learners.

3. Prudent Technology Adoption in Teaching

It is striking that the field of ESL/EFL has been notably slow to embrace technical innovations, with many educators and researchers still relying on extensive printed materials. In our discipline, much of the teaching content and materials remains derived from designs that are 20 to 30 years old, which often do not reflect current societal and technological trends. I am deeply committed to challenging this status quo and raising awareness about the responsible, appropriate, and scientifically informed integration of technology in language education. While I am a technology enthusiast, I do not assume that every teacher or learner must be familiar with technology. For instance, Voss et al. (2023) highlighted that generative AI has shown significant potential to transform language learning, teaching, and assessment. It has already been widely incorporated into the daily practices of language learners and test-takers at various levels. However, its integration into teaching agendas remains limited, with little guidance provided to students on when and how to use such tools wisely to support their language learning process. This lack of focus on purposeful facilitation by teachers and researchers means that the use of modern technologies such as generative AI is still largely dependent on individual student exploration, rather than being enhanced through high-quality guidance or structured support.

While the primary goal of ESL/EFL teaching remains the enhancement of language proficiency, technology serves as a powerful tool for facilitating efficiency, improving effectiveness, and enabling experiences that would otherwise be impossible in a traditional classroom setting. Thus, I incorporate technology only when it demonstrably enhances the teaching and learning experience. For example, I use digital tools to perform routine tasks, such as automated spelling checks, ensuring the grammatical accuracy of my slides, and sending out notifications—tasks that would otherwise be time-consuming if done manually by language teachers. AI Tools like ChatGPT help refine and polish my written content, and automated email systems streamline administrative communication. This selective adoption of technology allows me to integrate digital tools gradually, always mindful that many educators and learners may still be grappling with basic technological tasks, such as using smartphones or troubleshooting classroom projectors. I also experiment with more advanced technologies, such as AI and extended reality (XR), integrating them into lessons only when they align with the specific objectives of a module. The aim is not to overwhelm but to enhance learning by providing innovative experiences that might range from AI-generated instructional videos to immersive VR/MR simulations that reflect real-life language scenarios. As we stand on the brink of an era where technological systems are beginning to exhibit human-level intelligence or even surpass human capabilities in certain areas, such as effortlessly switching between languages, innovations like personal AI tutors and AR smart glasses with real-time translation and overlay features are becoming increasingly viable (Voss, 2024). I believe it is imperative that language educators do not remain passive observers. Instead, we must proactively explore and democratize these tools to enrich language teaching and learning. By doing so, I strive to make sure that my students, fellow teachers, and researchers are not only aware of these emerging technologies but are also equipped to benefit from their transformative potential.

References:

Brown, H. D., & Lee, H. (2015). Teaching by principles: An interactive approach to language pedagogy. Pearson.

Choi, L. J. (2022). Interrogating Structural Bias in Language Technology: Focusing on the Case of Voice Chatbots in South Korea. Sustainability, 14(20), 13177. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013177

Ellis, R. (2015). Understanding second language acquisition 2nd edition. Oxford university press.

Nunan, D. (2004). Task-based language teaching. Cambridge university press

Voss, E., Cushing, S. T., Ockey, G. J., & Yan, X. (2023). The Use of Assistive Technologies Including Generative AI by Test Takers in Language Assessment: A Debate of Theory and Practice. Language Assessment Quarterly, 20(4-5), 520-532. https://doi.org/10.1080/15434303.2023.2288256

Voss, E. (2024). Language assessment and artificial intelligence. In A. Kunnan (Ed.), The concise companion to language assessment (pp. 112–125). John Wiley &

Sons.

Summary

My teaching philosophy is rooted in a commitment to genuine, contextually rich language learning, tailored to the unique needs of my students and enhanced by strategic, thoughtful integration of technology. Through these approaches, I strive to transform language education into a dynamic, empowering, and forward-thinking discipline—one that anticipates emerging trends, embraces innovation, and truly prepares learners for the evolving linguistic landscape ahead.